“I was born in this house,” says Somprattana Na Nan, seated delicately in a chair on her teakwood, gingerbread-style balcony. “There used to be 20 or 30 people, lots of relatives living here. There were always people cooking, making northern-style food – curries, laap, things like that.”

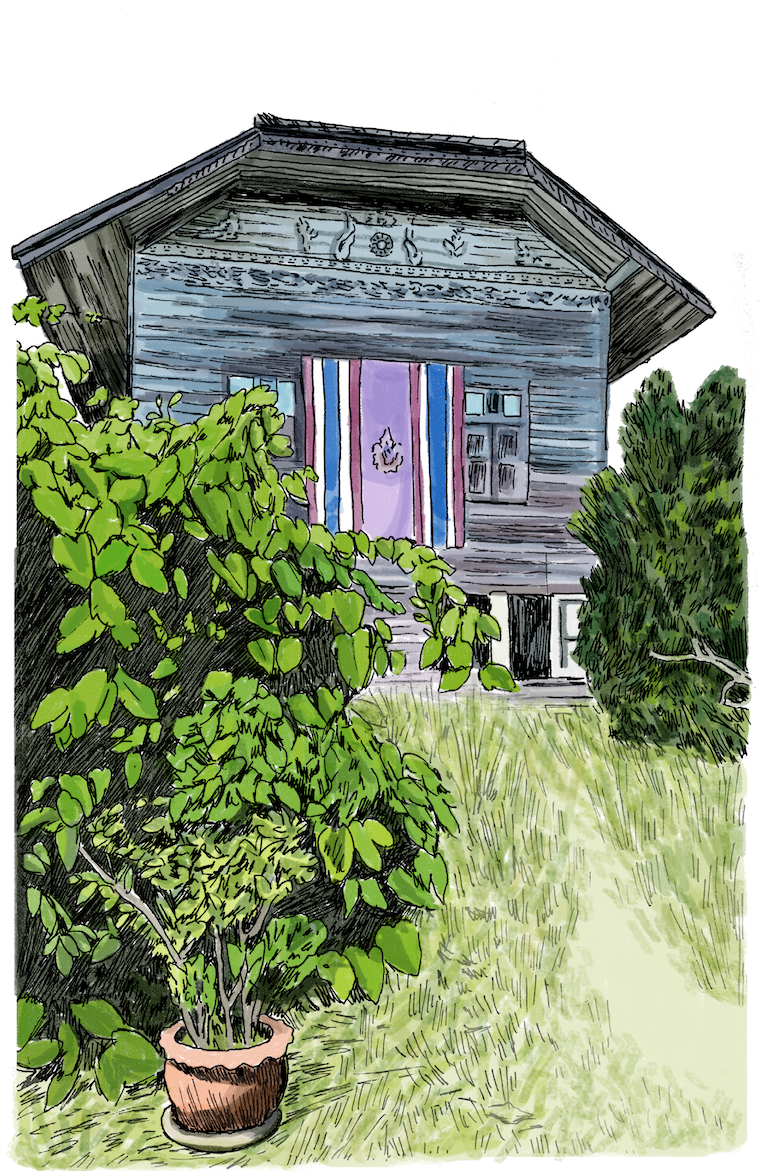

Faded, sagging, and in parts perilously dilapidated, Somprattana’s house has clearly seen better days. But the scenario she describes is not difficult to imagine. Spanning two floors, seemingly countless rooms, open-air walkways, a vast kitchen and a hidden location in an overgrown garden, Khum Ratchabut, as the house is officially known, is a thing of Southeast Asian fantasy. And not just for its unique architecture, but also for its links with northern Thai royalty.

In 1857, Somprattana’s great grandfather, Chao Maha Brahma Surathada, the 64th and final king of Nan, commissioned the construction of a vast golden teak mansion directly across from his palace (“They used to tell us that if you yelled from the front of the house, the back of the house wouldn’t hear you,” says Somprattana). In 1931, the king died, and soon after, Nan was fully – some might argue reluctantly – incorporated into the Kingdom of Siam. The king’s former mansion was subsequently disassembled, its teak planks retained and transformed into the home where Somprattana lives today, and along with them, one more legacy of those old royal days.

“We grew up eating dishes that people outside of the palace don’t know about,” she explains. “Such as kaeng sanat. Only people who are 60 years or older or who have a link with the palace would know this dish.”

Somprattana describes kaeng sanat as “a vegetable dish that happens to include pork”, and indeed, the hearty soup is all about plants and herbs, which range from astringent banana flower to tart preserved bamboo. Yet this very fact struck me as unusual for a dish of royal origin; shouldn’t there be more meat? More indulgence?

“Other dishes may involve only one or two ingredients, but this dish includes nine things,” says Somprattana, by way of explanation.

We have shifted to the kitchen at Khum Ratchabut, a cavernous wooden hall separated from the main structure by an elevated wooden walkway. Half of its space is dominated by a traditional northern Thai cooking area, a raised platform topped with sand and coal-burning stoves, which these days functions largely as a showpiece. Somprattana talks while adding vegetables and herbs to a vast and bubbling wok.

“I moved to Bangkok as a teen and lived there for 40 years,” she tells me. “I never made this dish until I came back to Nan, 20 years ago. I don’t have a maid here, so I had to learn to cook for myself. But when I was young I saw people making this food all the time.”

When she’s finished cooking, Somprattana and I eat at a wooden table hemmed in by piles of faded magazines and empty bottles, old photographs and a refrigerator from the 1940s. Kaeng sanat is, quite frankly, chunky and unappealingly monotone in appearance. But it’s also unique and delicious – pleasantly tart and salty – in both form and flavor quite unlike any other northern Thai dish I’ve encountered. Much like the house in which it was made, it could never be described as flashy, and you could say that it could use some work. But I’d argue that that’s part of its charm.

Kaeng Sanat

แกงสนัด

A royal curry of pork belly and vegetables

Serves 4

Ingredients

2 tablespoons black sesame

9 stalks water spinach (approximately 100 grams total), stalks only, tender leaves discarded

4 long beans (approximately 75 grams total)

30 grams tart, young tamarind leaves

4 large fresh red chilies (approximately 60 grams total)

1 small banana blossom (approximately 500 grams)

2 Thai white ribbed eggplants (approximately 300 grams total)

150 grams pickled bamboo, sliced thinly and rinsed in several changes of water

300 grams pork belly, cut into pieces approximately 1 inch square

1½ teaspoons salt

1½ teaspoons fish sauce

1 teaspoon fermented fish sauce

6 large cloves garlic (approximately 17 grams total)

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

Thai Kitchen Tools

granite mortar and pestle

Procedure

Prepare the black sesame: To a small wok or saute pan over low heat, add the black sesame. Toast, stirring frequently, until the seeds start to pop, about 3 minutes. When cool, add to a mortar and pestle. Pound and grind to a very coarse powder.

Prepare the vegetables: Cut the water spinach stalks and long beans into segments about 2 inches long. Halve each chili lengthwise. Peel and discard the exterior red leaves of the banana blossom. Halve the banana blossom lengthwise and cut the white, inner section of into strips about 1 inch wide. To a medium mixing bowl, add plenty of water, a dash of vinegar and the banana blossom (this will prevent discoloration). Score the eggplant deeply into quarters or eighths (leaving eggplant whole) and put in the same water as the banana blossom.

To a large pot over high heat, add 1 quart of water and the pork belly. Bring to the boil, reduce to a simmer and add the bamboo and banana blossom. Bring to a simmer, add the eggplants and long beans. Bring to a simmer and add the salt, fish sauce and fermented fish sauce. Bring to a simmer and add the water spinach, tamarind leaves and chilies. Close lid, reduce heat, and allow to simmer until fragrant and the vegetables are soft, about another 5 to 7 minutes. Add the black sesame, bring to a simmer. Taste, adjusting seasoning if necessary; the kaeng sanat should taste equal parts tart and salty, and should be fragrant.

While the kaeng sanat is simmering, to a mortar and pestle, add the garlic. Pound and grind to a coarse paste. To a wok over low heat, add the garlic and vegetable oil. Fry, stirring frequently, until garlic is golden, crispy and fragrant, about 10 minutes.

Remove to a serving bowl and garnish with the crispy garlic and garlic oil. Serve warm or at room temperature, with sticky rice, as part of a Thai meal.